Originally published on Shahrvand English (N° 14) – January 11, 2005

It is very easy for one who has never (or rarely) travelled abroad and visited foreign countries and cultures, to forget that one of, if not the, primary reason for travelling and going on such excursions is the expansion of one’s knowledge and experience, and the widening of one’s horizons and understanding. Thanks to the reflection of the mirror of travel, new light is shed onto what may have otherwise been a mystery and lacked explanation. Enlightenment dawns upon us with regards to matters which we may have otherwise not even thought about. And in the process we are able to understand a bit more about ourselves and we are able to blaze new paths for future understanding.

Recently, I had the immense pleasure of making a three week journey through France. I had never been to France in my life (save for the one time we had a stopover in Paris on the way to Madrid), and the only images I had of it in my mind were those propagated by our general Iranian views of what France would be like.

I suppose in a sense France has always been allowed to perch on a pedestal that has not been too far from the mythical (at least for me). It has always been the symbol and epitome of western democracy, art, and modernity. From the status of Paris as the pinnacle and nexus of modern art, literature, romance and everything else nice, to the legendary status of French cooking and wine, to cornucopia of French words which litter the landscape of the Persian lexicon, France and the French have always occupied a small place in our minds as well as our hearts. Suffice to say that I did not embark on this journey with an insignificant degree of expectation.

To say that I was not disappointed would be a sin. To say that I was overwhelmed would be an understatement. To say that I did not revel in (at times guilty) pleasure and enjoyment at every turn would be a downright lie. From the first time the smell of freshly baked croissants lifted me off the ground as we entered the ‘Châtelet’ metro station, to the infinitely many wines and bacchanalian pleasures that flowed into my memory, to the always-beautiful architecture of Paris and Lyon, to the endless roaming hills of Provence in the south, each of my moments were filled with wonder, admiration and enjoyment.

And in the course of it all I learned a great deal about the people of France and their way of life. The institution of eating that I witnessed, and the gastronomical renaissance that I experienced in my three-week journey, was simply a testament to the general attitude of life there, that the pleasures of life are just as important as the work and the obligations, and deserve the same amount of attention and investment.

There were many other interesting things which I would like to mention in testament to this thesis, but instead I will mention two in specific. I had always heard that France is world capital for finding books and music. And from what I saw, this is definitely the case. One cannot walk more than 200 metres on any street without walking by a used book store, or a giant book dealers which would Chapters-Indigo look like a convenience store. The most amazing thing, however, was that in every one of these venues, there was a huge section devoted entirely to comic books! Or to be more precise, Bandes-déssinées. For most Iranians who grew up in Iran, and read Tintin (or Asterix and Obelix) comics, this will be a familiar concept; just like the old Tintin books we grew up on, these large hardcover comic books, which tell the story in comic strips. The incredible thing was the range of these B.D.’s (as the French call them). They covered everything from kiddie stories (like Tintin) to more teenage-oriented ones, to satirical-political ones, to novellas, and even to more adult-themed stories. The quantity and range was truly fascinating. However this became less-surprising in light of another interesting observation.

The entire book is drawn out in minimalist, black-and-white comic strip style drawings.

One of the most noticeable things which I witnessed in my trip, was the omni-presence of graffiti on walls! I found it incredibly surprising. Not a wall was left without a mark. Even in Paris, which was a beautifully clean and white city, we could always find graffiti on walls in little alleyways of Montparnasse, to the little streets behind the Champs-Elysee, to tiny alley of Montmartre (the roaming grounds of Jean-Pierre Jeunet’s fairy-tale heroine Amélie). In fact at one point, as we were driving through the rocky terrain of the south France, near Marseille, where the roads are cut through the giant rocky terrain, I was able to spot some graffiti on the sheer walls of the cut rock, 50 metres above ground. Surprising as they may be independently, they make sense if we take them together. They simply amount to the fact that the French really enjoy their painted or drawn stories.

Let me be honest with you. All of what I have said to this point was to simply lay the ground work for the main point of this piece. And I’m proud to tell you, that we’ve arrived at the point where I can begin to get into the heart of the matter.

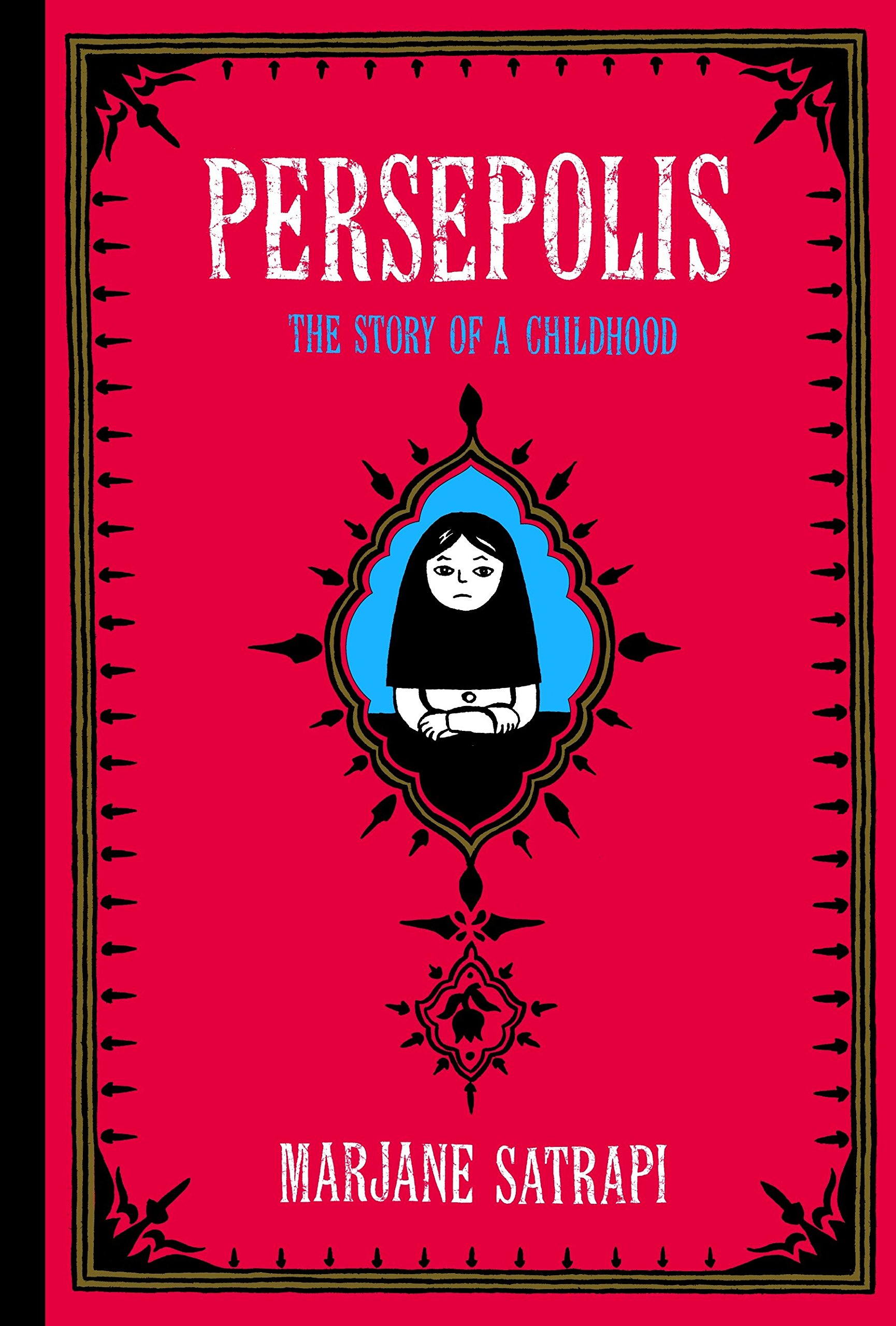

One of the nights we were there, we were sitting to dinner with some friends, all of whom were French, and the discussion moved onto Iran, from the current situation to the revolution and whatnot. As I struggled to understand what was being said, I heard the word ‘Persepolis’. My ears purcked up. As I strained further, I picked up the words ‘Marjane Satrapi’, and I understood what was being talked about. The discussion had turned to the critically acclaimed book by Marjane Satrapi, where she details an account of the 1979 Islamic revolution and years following it, through her 8-year old eyes. Since its publication in 2000, it has been hailed from all direction by critical acclaim, drawing comparisons to Art Spiegelman’s Maus, and other books of that ilk.

The entire book is drawn out in minimalist, black-and-white comic strip style drawings. The writing is very sharp and witty, and beautifully gives the account of Satrapi’s life during those years. It is of particular interest since she was a daughter of two Marxists, a group of ideologues who, during the revolution, were heavily persecuted (and in many cases, executed). After being born in Rasht, by the Caspian coast, she moved to Tehran with her family, where she attended the Lycée Francais and the school of Beaux-Arts (fine arts) in Tehran, before leaving for Vienna, Austria for schooling. She then moved to Strasbourg, in the north-east of France to study Art Deco.

She currently resides in Paris, and since the 2000 release of Persepolis, she has put out three sequels, detailing her other experiences during the Islamic regime, the Iran-Iraq war and separation from her parents in Europe. In addition, her latest comic book-novel titled “Poulet et Prune” (Zereshk ba morgh), is the tragic yet comic story of an Iranian man who becomes depressed and lets himself die after his beloved tar is destroyed. Despite all the critical acclaim that the Persepolis series has garnered, some critics hail this latest work as her magnum opus to-date.

The striking thing I found about the phenomenon that has become these books, or B.D.’s to use the correct terminology, is the depth to which they

have been able to delve within the French culture and especially among the youth. On two separate occasions while dining at restaurants in France, I saw young people sitting at a table with a copy of the Persepolis book, loaned out from a library, by their side. The friend who first brought up the book – to my surprised – mentioned it in response to an incorrect comment by another friend at the table, with regards to the Iranian revolution and the Iran-Iraq war.

The fact is that Marjane Satrapi has been able to curve a niche for modern Iranian history in one of the cultural centres of the occident. Behind the façade of simple black and white caricatures of girls and women in chador and men with five-o’clock shadows, she has managed to chronicle the Islamic revolution of Iran through the eyes of one who lived through it; through the simplicity and elegance of a comic strip she has been able to reach the youth and the curious, and to dispel the myths and misconceptions about a country whose doors have been closed to outsiders for the last 26 years, and filled that void with simple truths and more importantly, with experiences.

The one lesson that we can learn from Satrapi’s pioneering work, is that we don’t need to write long and magniloquent books, analyzing the theories behind the reasons as to why the people did so and so. Perhaps such works are needed too, but we need to find a way to reach out to those who know the least about the truth and bring it to them through human experience and in a palatable manner, as opposed to preaching to the converted, as we usually tend to do.