In the tradition of Taoism, the famous Yin-Yang symbol (correctly known as the T’ai Chi symbol) is a philosophy all unto itself. It speaks of the seed of light being planted when darkness is at its peak; of the root of Black growing in the heart of White. Whether we believe in this philosophy or not, we see it everywhere and it is a part of all cultures. One such case is the celebration of the ancient Iranian festival of Yalda.

The night of December 21, is the eve of the first day of winter, the Winter Solstice. As such, it is also the longest night of the year. This night, in one form or another, has been a part of every culture and civilization in the history of mankind. Everywhere it has a different name, and the reasons may also differ, but the ideas are all rooted in the same ground. The most ancient civilizations, including the Persians, commence their solar year on this night. For example, the Egyptians celebrated the birth of the Sun, with a twelve day festival starting on this night (twelve, to correspond to their division of the solar year).

For Iranians, it has long stood as a night of Birth, and Beginning. In the ancient tradition of Mithraism (alternately written Mitraism), it heralded the birth of Mitra, the deity of the Sun, or Light. In fact, Yalda is the eve of the birth of Mitra.

The name ‘Yalda’ is a Syriac word. Although the time and place of its importation into Persian is not known, it is believed that it took place when many of the early Christians, fleeing from Roman persecution, took refuge in Sassanian-ruled Iran/Persia. The word means birth and the Persian words “taval’lod” and “meelaad” are derived from it. The original name for this night was and still is, ‘Shab-eh Cheleh’. The word literally means the fortieth night; in this case referring to another Persian celebration named ‘Sadeh’ which takes place forty nights after Yalda.

Upon its entry into the Persian culture, this festival merged with the Zoroastrian religion of the time and transformed into the celebration of the victory of Ahura Mazda over Ahriman on the night when Ahriman is at his peak.

The first day after Yalda is named ‘Dey’. This day is also the beginning of the month of ‘Dey’ and is a festival by the name of ‘Deygan’. It is a celebration dedicated to the pre-Zoroastrian deity ‘Dey’, which was a creator-deity who was later changed into the god of Light (which is where the English word ‘day’ comes from). In the Zoroastrian tradition, this day is dedicated to Ahura Mazda.

On the evening of ‘Shab-eh Yalda’ families will get together and light fires to help in the defeat of Ahriman. Feasts will be had, and prayers will be offered to ensure the victory of the Sun and Light (which would be essential to the protection of the winter crops). Since the belief was that Mitra was born of the light that came out of this Alborz mountains (in the north of Iran), ancient Iranians would gather in caves along the sides of this majestic mountain to witness the rebirth of the sun at dawn (these folks were known as ‘Yaar-eh ghaar’ meaning ‘Cave Mate’).

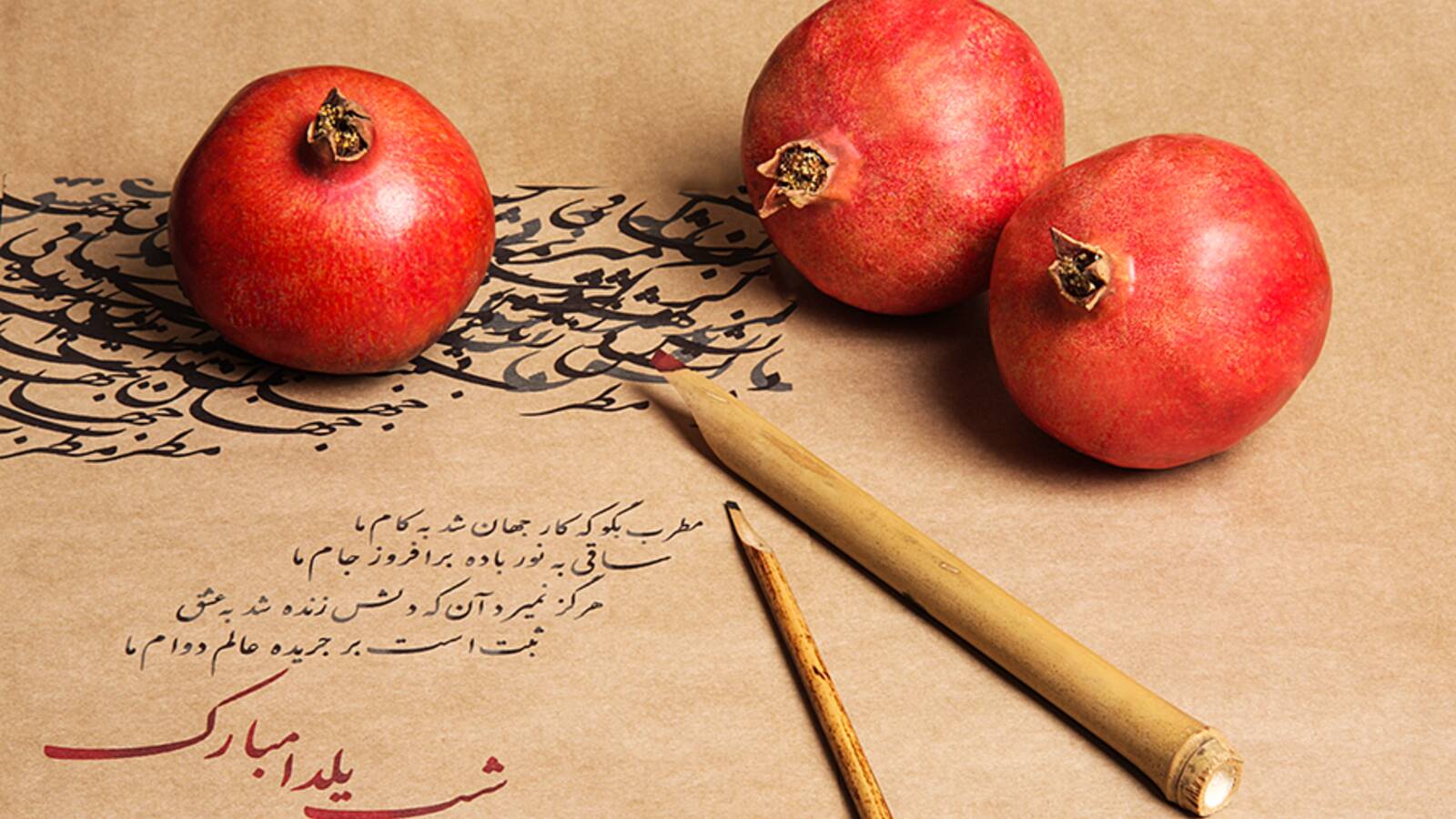

Part of the feasting of this night included the eating of various nuts (‘Aajeel’) and dried and fresh fruits. Other foods would include rice, watermelon, saffron, yoghurt, and chicken; each with their own symbolism.

Another interesting aspect of the early form of this festival was the temporary subversion of order. Kings dressed in white would walk among the people; servants and masters would switch roles and mock kings would be crowned. It is believed that these practices endured even through the Sassanian reign. In fact, much of this was later passed onto and practiced by the Romans.

As the religion of Mitraism spread from ancient Iran, and spilled over into Rome and other European countries, it was slowly turned into the official religion of many regions and peoples. When Christianity began its dominance and sweep across Europe, the church found that they had trouble changing some of the ancient Indo-European traditions and festivals, included Yalda.

Thus they adopted an if-you-can’t-beat-them-join-them policy and decided to transform this ancient festival into a Christian one. At that time, the birthday of Jesus (or rather the baptismal of Jesus) was accepted and believed to be on January 6 (a belief that the Orthodox Christians of Eastern Europe still cling to).

However, by the forth century, the Church, seeing the power that the old Pagan festivals held over the people, decided to take advantage and agreed to celebrate the birth of Jesus on the 25th of December (indeed, the 25th is not on Yalda or the winter solstice. This, however, is due to mistakes in counting days over the years, and thus Christmas falling four days later).

In fact, this should not really come as too much of a surprise, considering the number of aspects that are shared between Yalda and similar festivals, and Christmas (not the commercial notion of Christmas, which is what we have now, but the more true and traditional version of the celebration), such as the exchange of gifts and bringing of greenery into the home, among others.

All external ornamentation put aside, festivals such as Yalda were reasons for people to come together, to celebrate Nature and Life, and to bring hope and light into the hearts and lives in the darkest and longest hours of the natural year. As always, the seed of life, growth and birth, planted on the eve of the first day of winter, and sown into the very zenith of darkness.

(Originally published in Shahrvand English (N° 12) – December 21, 2004)